II. CHINESE GRAFFITI ART

Adriana Iezzi

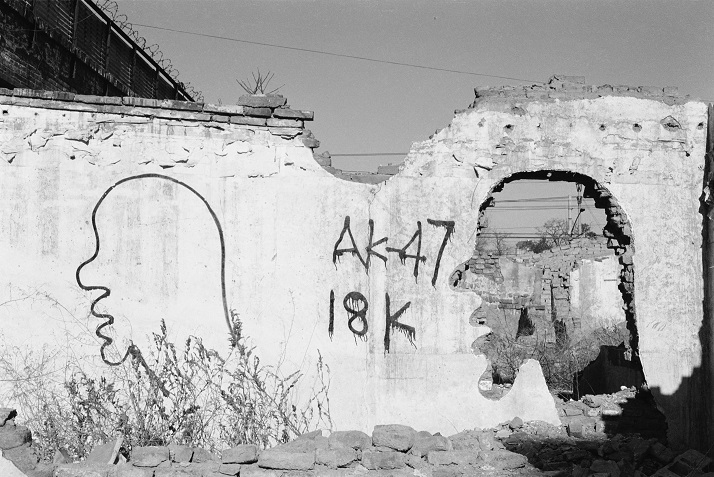

Chinese graffiti art is a recent phenomenon with very unique features. It emerged in the mainland in the mid-1990s, only to spread and gain visibility from 2005 to 2010 (Valjakka 2011, p. 73). Its breakthrough is usually traced back to the work of one artist in particular, Zhang Dali 张大力(Harbin, 1963). In 1995, he flooded the city of Beijing with his massive art project Dialogue and Demolition (Duihua yu chai 对话与拆, 1995-2005) (Fig. 2, p. 36), involving more than 2,000 giant portraits of his own profile spray-painted on soon-to-be-demolished buildings. His tags1Tag (qianming tuya 签 名 涂 鸦) – The pseudonym, stage name, or code name that every graffiti artist, mc and breaker uses to distinguish themselves, to stand out and highlight their presence in the city. Being the most basic form of graffiti, created with spray cans or markers, the tag is the backbone of the writing phenomenon. The evolution of the tag represents the personal style of its author. All pieces, even the largest, most colourful and elaborate ones, remain, in essence, signatures. The activity of marking a surface with a tag is called tagging-up, while tag bombing is the reproduction of one’s tag on a large scale in a certain area of the city. Tags can also be representative of entire groups. Different writers or mcs who join together can decide to use one comprehensive tag, as a symbol of the group (see Crew). AK-47 (initials for Kalashnikov) or 18K (initials for 18-karat gold) (Pizziolo, Rovasio 2009, p. 8) were his signature. There is no consensus of opinion on this pioneer of Beijing graffiti art (who will be discussed in depth in the third chapter). While acknowledging the powerful driving force of his work, some (especially young writers2Writer (tuyazhe 涂鸦者 / penzi 喷子 / tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家 / xieziren 写字人) – An artist who executes graffiti mainly based on lettering.) consider Zhang Dali an artist who devoted only part of his career to graffiti3Graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) – A worldwide social, cultural and artistic phenomenon born in the 1970s in New York ghettos as a spontaneous expression, with no declared intent, of a heterogeneous group of young people belonging to the hip-hop subculture. The etymology of the word graffito derives from the Latin gràphium, or “style of engraving”, which in turn stems from the Greek gràphein (γράφειν, to scratch, to hollow, to draw). The English term “writing”, instead, stands for the act of creating one’s tag in public spaces using spray paint or markers. It entails a study of lettering, namely the style of the characters that make up both simple tags and pieces. In China, the term “graffiti” does not only refer to the writing of letters or characters as in writing, and thus graffiti is also called tuya yishu 涂 鸦 艺 术 (lit. graffiti art), implying a wide range of artistic expressions on public soil (making it much closer to street art). Another term used is tuya huihua 涂 鸦 绘 画 (lit. graffiti painting), which refers to graffiti containing puppets..

Another important artist is often mentioned alongside the figure of Zhang Dali as a (hypothetical) forerunner of Chinese graffiti art. This is Tsang Tsou-choi (Zeng Zaocai 曾 灶 財, 1912-2007), better known as King4King (wangzhe 王 者) – A sort of leader for other writers. Generally, the king is the best skilled writer most respected by everyone. A writer is deemed king only if another king recognises him or her as such. Factors taken into account for this title are the number of pieces made in a city, style, originality, and experience. of Kowloon (Jiulong Huangdi 九龍皇帝), whose artistic activity was based in Hong Kong (Pic. 27). Tsang Tsou-choi was born to a family of poor farm workers in a small village in Guangdong, a province on China’s southern coast with Canton as its capital. At the age of 16 he moved to Hong Kong, where he began his self-taught studies. In 1954, armed with brush and ink, he started bombing the city streets and avenues with insulting writings, an activity he would carry on for the rest of his life (Clarke 2001). The content of his works is rather obsessive: in his “calli-graffiti”5Calli-graffiti or calligraphy graffiti (shufa tuya 书法涂鸦) – An urban art form that combines calligraphy and graffiti. (calligraphy-style graffiti) he almost unalterably and compulsively repeats a predetermined line-up: his name, the title he ascribes to himself (king/emperor of China or Hong Kong or Kowloon), a list of about 20 of his ancestors, the name of some illustrious Chinese emperors, and a series of outrageous expressions against the British crown, proclaiming each nation’s right to sovereignty (Zhang 2011).

The artist is convinced that in ancient times the district of Kowloon, the most populous in Hong Kong and the one where he has made the majority of his writings, belonged to his ancestors, as allegedly confirmed by the discovery of important documents. Thus, the calligraphic pieces he systematically creates around the city on all kinds of surfaces represent an act of war against the British government, which, according to Tsang Tsou- choi, has been usurping part of his ancestors’ land, since they annexed it to the British domain without his family receiving any compensation. That said, the fact that he does not use the conventional means (spray cans) and contents (tags) of graffiti writing to bring his urban works to life, on the one hand makes his art unique, and on the other differentiates it from the peculiar methods of this art form, bringing it rather closer to the art of calligraphy.

This makes it easy to understand why he is not universally considered the father of Chinese graffiti. His works are defined in the most diverse ways: they’re usually called “calligraphy graffiti” (shufa tuya 书 法 涂 鸦) (Zhao 2012), but also “character graffiti” (wenzi tuya 文字涂鸦) (Zhang 2011) or more generally “calligraphic works” (shufa zuopin 书法作品), “writing works” (shuxie zuopin 书写作品) and “graffiti art” (tuya yishu 涂鸦艺术). These five definitions highlight how difficult it is to frame his art, which stands midway between graffiti and calligraphy. Moreover, Tsang Tsou-choi is active in Hong Kong, which until 1997 was not part of the People’s Republic of China founded by Mao Zedong in 1949, but was a British protectorate, and thus not directly traceable to actual China.

Hong Kong: a hub of development and diffusion

Despite these distinctions, Hong Kong has unquestionably played a crucial role in the spread of graffiti in China, especially the “purest” form of graffiti writing. There is no doubt that writers populated this city from as early as the first half of the 1990s, and that this climate has had a strong influence in the diffusion of graffiti in the People’s Republic of China6A documentary entitled Great Walls of China (Pearl Channel, 2007) highlights the presence of several writers in Hong Kong before the mid-1990s. (See Valjakka 2011, p. 74).. MCRen (MC 仁) is one of these writers7Writer (tuyazhe 涂鸦者 / penzi 喷子 / tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家 / xieziren 写字人) – An artist who executes graffiti mainly based on lettering.. In an interview, he claims to be the “first writer in Asia” (Valjakka 2011, p. 90): he does not recognise the King of Kowloon’s status as a true writer, and he was active in Hong Kong long before Zhang Dali in Beijing.

A number of writers working in China, like Dezio (Sanada, Hassan 2010, p. 14) and Tin.G, affirm that the origin of Chinese graffiti is to be traced back to Hong Kong. And even certain scholars of the phenomenon believe that graffiti originally spread from the south as a result of foreign influences in Hong Kong (Sanada, Hassan 2010, p. 11; Lu 2015, p. 31). Soon after the city returned under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China, some nearby cities paved the way for graffiti art to influence the rest of China. After 1997, many Hong Kong graffiti writers came to Shenzhen, a city located right at the northern border. Hong Kong had just been opened, thus allowing these artists to move from one region to another (see Video section, Hassan 2010). From there, in 1998 they reached Guangzhou, a megalopolis located north of Shenzhen (Sanada, Hassan 2010, p. 14). Unlike in most other countries, especially in the early stages of the phenomenon’s development, in China graffiti spread most significantly in minor centres, such as Chengdu and Wuhan (located halfway between Chengdu and Shanghai), because in metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai control by the authorities was greater (ivi, p. 11).

However, the speed and extent to which graffiti has spread throughout the country have been significant, especially since the early 2000s. Driven also by the newly arrived hip-hop8Hip-hop (xiha 嘻哈) – A cultural movement that emerged predominantly in the Afro-American and Latino communities of the Bronx in New York, in the late 1970s. The four main aspects or elements of hip-hop culture are speech, music, movement and sign: MCing (shuochang 说 唱), or rap music introduced by Afro- Americans (MC is the acronym of Master of Ceremony); Djing (dadie 打 碟), introduced by Jamaicans; graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) and breakdance (diban wu 地板舞 o pili wu 霹雳舞), introduced by Puerto Ricans. culture (Valjakka 2015, p. 76), as from 2005 graffiti reached Beijing and Shanghai, where it experienced a peak in popularity between 2007 and 2013. During this period, particularly between 2008 and 2012, two Hong Kong graffiti writers, Xeme and Sinic, organised the world-famous Wall Lords Graffiti Battles, the most important graffiti jam sessions at the Chinese and Asian level: every year, several Chinese and non-Chinese crews9Crew (tuandui 团队) – In hip hop culture, a circle of people collaborating on artistic or cultural projects, e.g., a group of writers or dancers. In graffiti writing, a crew is an organised group of writers who paint together to create pieces. They are usually friends, meaning they share mutual esteem and respect. A writer may belong to more than one crew over time, or even at the same time. The name of a crew is normally an acronym of two or three letters, possibly having multiple meanings. Like tags, crews’ names are often written on the side of the piece, or they form the very core of the piece, with the name of the crew members dotted all around. would participate, showing the highly technical and expressive level they had achieved (Valjakka 2016, p. 369)10The competitions were held annually both at the national level, with the participation of Chinese crews only, and at the international level, with crews from the Philippines, Singapore, Japan, Korea, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan. The winning crew of the Chinese contest was entitled to participate in the international competition. The ABS crew’s (see Ch. III) victory in the Pan-Asian contest in 2011 shows the high-level technical skills achieved by the Chinese crews.. However, their success was short-lived. Between 2014 and 2015, particularly in Beijing and Shanghai, graffiti art gradually started to decline, mainly due to the government’s repression of this art form and to economic pressure, which led to the demolition of graffiti places and their replacement with modern residential neighbourhoods or commercial areas. It should not be forgotten that in 2013 Xi Jinping became President of the People’s Republic of China, initiating a policy of ever-growing control over civil society, also widely implemented by the five-year plan launched in 2016. China experienced an increasingly authoritarian rule starting in 2017, when the President’s political thought became an integral part of the Chinese Constitution.

Unfortunately, this kind of policy persists to this day and the Chinese graffiti world continues to bear the consequences, leaving little room for the critical voice and freedom of writers. The choice is to bow to the rules of economics, forming commercial partnerships and working on commission, or to stop making graffiti on the streets.

Legal and illegal art forms

Since it was introduced in China, graffiti has acquired distinctive features that set it apart from western graffiti. The first major difference lies in the fact that in China graffiti is not strictly regarded as a form of vandalism, a criminal act or a manifestation of class conflict. Although Chinese law prohibits writing and drawing on urban public spaces, court officers are usually tolerant of writers, as long as their works are not too eye-catching, do not go viral, and are not offensive (Valjakka 2011, p. 82). Punishments against them are mostly limited to paying fines or cleaning the defaced walls (Valjakka 2015, p. 263).

In China, graffiti is often referred to as “half legal and half illegal” (Bidisha 2014). Unlike in western cities, there is a distinct scarcity of tags in public transportation areas (the place where graffiti originated and are mainly found in the West) and in urban spaces, with the exception of contemporary art districts, including Beijing’s 798 Art District and the Moganshan Road area in Shanghai. Bombing11Bombing (zhajie 炸 街 / beng 崩) – Filling walls and trains with illegal graffiti, typically throw-ups, tags, stencils or simple lettering pieces that can be executed quickly. This is the favourite practice of writers whose primary aim is quality, and who cover the city with their tag to attain the fame of king. trains with graffiti, particularly underground cars, is a very common practice in the West, while in China it is extremely rare. In southern cities a few writers occasionally try to break the rules, but this is quite exceptional due to fear of repercussions from law enforcement agencies. Damaging public places of great visibility (such as the underground) makes the police less tolerant (Valjakka 2011, p. 82). Writing on trains or any other government property is absolutely forbidden and considered an overtly subversive act. The risk is that of being detained by the police or placed under surveillance, and immediate expulsion from the country for foreigners (Valjakka 2015, p. 264).

In spite of their revolutionary intent against the homogenization and dreariness of cities, vandalism and the illegal side of graffiti have resulted in writings being outlawed along the underground or on any other form of public transportation. As a result, Chinese graffiti writing has been emptied of its underground nature. However, in every Chinese city there are “semi-legal” walls on which graffiti writers can bring their pieces to life without police intervention. These are not halls of fame12Hall of fame (tuya qiang 涂 鸦 墙) – A space where graffiti writing is (more or less) legal. Halls of fame are mainly popular with writers who aim to create artistic, sophisticated pieces, favouring quality over quantity and constantly searching for original styles. authorised by the government, but walls on which writing graffiti is not illegal. Chief among them is Honghu West Road in Shenzhen, where the first graffiti appeared between 2002 and 2003 (ibid.). Other prominent “semi-legal” walls are Moganshan Road in Shanghai (see Ch. IV), Jingmi Road in Beijing (see Ch. III), Fuqing Road in Chengdu (see Ch. V), Mong Kok Alley in Hong Kong, and Huangjueping Street in Chongqing. Consequently, most graffiti in China, especially those placed in highly crowded areas, are apolitical (ivi, p. 265) and devoid of any message of social protest. On the contrary, graffiti is sometimes created precisely in support of government political messages, like the pieces that appeared all around Beijing before the 2008 Olympics to promote the momentous event and propagandise the image of a rich, powerful and prosperous country. One striking example is Olympic Beijing by the Kwayin Clan, described below (Fig. 8).

Similarly, in the same year, the graffiti made by Tin.G (see ch. IV) and Moon, a graffiti writer from Quanzhou in the Fujian Province, responded to the heated debate among foreigners calling for greater autonomy for some regions of China (Tibet, in particular) with a double inscription in English and Chinese, One China Forever (Yi ge Zhongguo 壹個中國), on Moganshan Road, reiterating that China is, and always will be, one and indissoluble (Valjakka 2015, p. 266). Interestingly enough, these are all personal initiatives of the writers themselves, not mandated by the authorities but actually spontaneous. This is not to say that there are no expressions of protest among Chinese writers. Albeit very rare, these are usually rendered abstractly or through complex visual references, and generally made in barely visible, hard-to-access places like abandoned buildings (ivi, p. 265).

As it is not considered an act of vandalism, graffiti in China appears as a pure form of artistic expression (primarily in the eyes of the writers), and the contemporary art system has strongly supported its development since its inception, particularly in Beijing and Shanghai. Contemporary art districts have become the main graffiti “hubs” since they are among the few places where writers have always been free to bomb and make elaborate pieces. Graffiti-related exhibitions and events aimed at encouraging and giving visibility to this art form have been held in such districts from the very beginning (Valjakka 2011, pp. 78-80). Among the most prominent was the exhibition Art from the Streets (The History of Street Art – from New York to Beijing)13Art from the Streets (The History of Street Art – from New York to Beijing) is the title of the exhibition by the Department of Mural Painting of the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) and the CAFA Art Museum, in collaboration with Shanghai’s Magda Danysz Gallery, held at the 3B Exhibition Hall of the CAFA Art Museum from 1 July to 24 August 2016 (https://www.cafamuseum.org/en/exhibit/detail/530). Curated by Tang Hui and Magda Danysz, the exhibition welcomed international graffiti writers from Brazil, China, France, Italy, Portugal, Senegal, the United States and the United Kingdom and presented the catalogue Street Art, a Global View available at: https:// issuu.com/magdagallery/docs/digital_catalogue_3., where Chinese writers could show their pieces along those of the likes of Banksy, Blek le Rat, Invader and Shepard Fairey. Another important point of contact between the world of graffiti and the world of art is the artistic background of most Chinese writers: they are mostly art school or academy students, designers, or young people working in the creative industry (ivi, p. 80). As a result, many of them also transpose their style into graphic design works made on a temporary support or canvas. Indeed, it is not uncommon for graffiti writers to become fully-fledged artists. Fan Sack, discussed in the last chapter, is one such artist. Unlike in the West, in China, the osmotic nature of these two worlds makes it easy to switch sides.

Middle-class experiments and on demand professionals

The primary functions of Chinese graffiti do not include rebellion, but individual expression and embellishment of urban spaces. In particular, many new-generation Chinese graffiti writers, especially in Beijing, use walls as canvases on which to pour their artistic expressiveness, enlivening their pieces with numerous purely fictional figurative elements, such as ghosts, dragons, animated mushrooms and cartoon characters (Valjakka 2011, p. 75), thus leveraging a greater creativity instead of simply combining letters.

This is because graffiti constitutes a form of escape from reality for many youths who come from middle-class or wealthy Chinese families, very far from the New York ghettos of the 1980s. In fact, for a good deal of them it is kind of a short-lived hobby: after a couple of years (or even less) most of these writers stop their activity (Valjakka 2016, p. 367) due to strong family pressure to find a “real” job and fit into the social fabric.

As a result, the number of active Chinese writers is small when compared to the number of inhabitants, which explains why the graffiti scene has never fully developed, despite some writers being very talented and technically proficient (Valjakka 2015, p. 263). According to Andc, leader of the ABS crew, at the peak of its development between 2013 and 2014 there were about 500 professional writers in China, mainly in Beijing and Shanghai, but only about fifty or less had good writing skills (for Andc see Tung 2013; Wu 2014). By 2015, as the decline began, the estimated number had already dropped to 350 – 250 (ibid.), while today it has halved. The Chinese view of graffiti as an art form, partly due to the aforementioned skills of many writers, has encouraged the tendency to make paid or commissioned works, in contrast to the West, where most writers claim that only illegal writings are worthy of being called graffiti (Valjakka 2011, p. 82). In China, on the other hand, it is quite common for writers to collaborate with national or foreign commercial brands for advertising campaigns or new store openings and other promotional initiatives. For example, the crews covered in this volume have undertaken countless collaborations with renowned brands. For many of these writers, especially at the beginning of their career, commercial collaborations were just a way to earn money to be reinvested on the street. Subsequently, they turned out to be a springboard to establish actual companies specialised in commercial graffiti making. One of the first to grasp this opportunity was the ABS crew (see Ch. III), followed by others in Beijing, such as the DNA and Tuns crews. Another is the CGG crew, of which Tin.G is a member (see Ch. IV), and which brings together female writers from Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Hainan. Gas also followed their example, opening a spray-paint store in Chengdu and establishing a business partnership with another writer, Seven, with whom he still creates works on commission (see Ch. V). For Chinese writers, this seems to be the only way to survive and not disappear. Moreover, the exponential growth of their business activities goes hand in hand with a dramatic decrease in illegal street activities, and you can easily guess why.

It is also important to note that Chinese writers, although belonging to different crews, are first and foremost friends. There is no real “territoriality” or street warfare as in the West. On the contrary, artists exchange ideas and even materials, generating a large community in which absolute freedom of expression prevails. In this atmosphere, sharing becomes the humus of art, and freedom makes the soil of creation fertile.

Charactering and figurativism: Chinese style lessons

With regard to stylistic research, Chinese graffiti has undoubtedly always imitated Euro-American styles (Valjakka 2011, p. 84), and even today most styles draw inspiration from the western tradition (Valjakka 2016, p. 368). This also results from the presence of the foreign writers who have operated (and continue to operate) in the Chinese metropolises, regularly collaborating with local writers: they have conditioned the Chinese scene, making it much more international. In Beijing, for example, mention should be made of Zyko (Germany), Aigor (Europe), Sbam (Italy) and Zato (USA); and in Shanghai, of Dezio (France, Pic. 19), Fluke (Great Britain) and Diase (Italy). These writers have lived and operated in China for a long time, strongly influencing its scene.

Nevertheless, an attempt to develop a Chinese style has been evident from the earliest stages of graffiti development in China, defining the work of some crews and several writers. A significant sign of this attempt is the use of Chinese characters instead of Latin letters. Thus, we will no longer speak of lettering14Lettering – The style of the letters, and the pivotal concept of graffiti writing. Writers first and foremost paint letters, which may differ in size and style: block consists of large, square or rectangular letters, usually filled with one colour; soft consists of round, soft, cloud-like shaped letters, usually of one colour within an outline; in bubble style, the letters look like soap bubbles, very precisely coloured and with a wide outline; in wildstyle, the letters are composed of intersecting three-dimensional arrows, which give the idea of movement and confusion. In the case of Chinese graffiti art, since many writers also use characters in their pieces, a new term was coined to indicate the style of the characters: Charactering., but of charactering15Charactering – Term we have coined to designate the style of characters in writing pieces (see Lettering), or the use of Chinese characters in graffiti.. Charactering is a neologism we have coined to refer to the character style in Chinese graffiti, since many writers do not use the Latin alphabet. Graffiti made of characters are extremely difficult to compose because they do not follow fixed rules: while western writers develop (and practice on their sketchbooks16Black book or book (shougaoben 手稿本) – The writer’s draft book.) their own lettering that can be repeated for any type of writing, in Chinese this is not possible because each character is written differently. Therefore, every time writers need to create a new way of portraying each character and harmoniously connecting it to the others in a consistent way. To do this, considerable familiarity with the use of the spray-can and a great deal of creativity are essential, especially if one wants to use wildstyle17Wildstyle (kuangye fengge 狂野风格) – A complex composition of letters assembled to give a unique shape and dynamic to the piece. In this style, the letters are distorted and superimposed, and sometimes enriched with three- dimensional arrows, tribals, pikes, puppets and other decorative elements that give an idea of movement and confusion. This style can be straight or soft: the first is symmetrical, and the arrows forming the letters draw sharp angles; the second is asymmetrical, and the angles are replaced by curved arrows with rounded points. To increase the perception of depth, in addition to inserting junctions between characters, the entire word structure can be turned into a three-dimensional element. This complicated construction of interlocking letters is considered one of the hardest styles to master and the lettering of the pieces done in wildstyle is often completely undecipherable to non-writers. and the 3D (three-dimensional) style.

In addition to charactering, the use of visual elements evoking Chinese culturelike dragons, pandas and lanterns, sometimes creatively restyled, is another feature we find in many of the graffiti made in China. Those who were perhaps most successful in pushing the pursuit of a Chinese style are the Beijing Penzi and the Kwanyin Clan in Beijing (see Chapters IV and V), as they have been able to fill their works with elaborate visual references to their home culture (Valjakka 2015, p. 271).

Other artists that often combine Chinese characters and Latin letters are the Oops crew and Popil from Shanghai (see Ch. IV). Popil is a writer and illustrator who uses yoga postures to shape the “Letter girl” that underlies her lettering (Walde 2011).

In Beijing and Shanghai, some foreign writers also try to use Chinese characters in reference the local language: the first is Dezio, known in Shanghai for his elaborate pieces in which he uses his Chinese tag (Duxi’ao 度西奥) (Valjakka 2016, p. 363), and the second is Zato, who has covered Beijing with both his Chinese tag (Zatuo 杂 投) and other mysterious Mandarin writings.

But this kind of research is not only limited to Beijing and Shanghai. The Chengdu-based writer Gas consistently makes use of Chinese characters in his works, choosing words that recall relevant concepts of Chinese culture (see Ch. V). In Shenzhen there is Touchy (a.k.a. Touch), who creates extremely elaborate charactering pieces that are difficult to decipher even for native speakers. He heavily reshapes different sized characters, written in random order and with mixed colours, to condemn the deceiving messages of the growing advertising industry (Valjakka 2015, p. 273). In Hong Kong, both Xeme and Sinic, two brothers well known in local circles, use Chinese characters in their pieces and sometimes draw inspiration from traditional calligraphy (Johnson 2008). Other writers who regularly make use of characters are Mora (Chen Shisan 陈十三) from Guangzhou, Moon (Yue xia 月下) from Quanzhou (Fujian province), Exas (Lingdan 灵丹) and Zeit (Shijian 时 间) from Beijing (Mouna 2017), each of them following their own personal style. China’s internal graffiti scene, therefore, is utterly diverse and very different to the one we are used to. Its in-depth analysis can provide us with an interesting interpretation of some of the salient features of the local youth culture, alongside the chance to discover unprecedented aspects of modern-day China.

Terminology issues

Exploring how graffiti is defined in China today allows us to understand how complex and rich in specific features the phenomenon is. While it may seem a purely terminological “niche” issue for philologists or sinologists, it reveals much about what graffiti represents in today’s China and how it is perceived. The most commonly used term in colloquial slang to define graffiti is tuya 涂鸦, a word that literally means “poor handwriting, scrawl”, such as by a child: what we would call “chicken-scratch”. The word is composed of two characters – tu 涂 “spread on, scribble” and ya 鸦 “raven”– and derives from two lines of a poem by the Tang dynasty (618-907) author Lu Tong 卢仝 (795-835), where he tells how his son, as a child, used to enjoy scribbling in his books in raven ink18The term tuya derives from the verses Hu lai an shang fan mozhi, tumo shishu ru laoya 忽来案上翻墨汁,涂抹诗书如老鸦 (And suddenly, the ink was poured over the table, and poetry was smeared in raven black).. The original meaning of the word thus takes on slightly negative connotations, creating a parallelism between graffiti and children’s attempts at writing. Consequently, the local media tend to prefer the term tuya yishu 涂鸦艺术, or “graffiti art”, thereby elevating this form of expression to artistic status by emphasizing the strong interconnection between graffiti and the art world, as previously explained.

There are several further definitions with different nuances: both the local press and writers sometimes speak of jietou tuya 街头涂鸦, or “street graffiti” (Valjakka 2015, p. 261; Llys 2015), referring exclusively to mostly non- legal graffiti in urban contexts and emphasising the link with the street as the preferred place for graffiti. The use of this expression highlights how, in China, it is by no means obvious that graffiti is done on the streets, as it can just as easily be found in other locations (exhibitions, store and clubs interiors, merchandising and designer objects) that are entirely legitimate and recognised as such.

Occasionally, they are also referred to as tuya huihua 涂鸦绘画, or “graffiti painting/drawing” (Valjakka 2011, p. 77), to underline how each piece is perceived as an authentic painting primarily representing a decorative feature of the urban context, where the presence of figurative elements is always welcomed. In relation to this definition, there are other expressions like jietou qiangti caihui 街头墙体彩绘, meaning “street murals”, or shou hui qiang hui 手绘墙绘, signifying “hand-painted murals”, occasionally adopted to express the idea of urban decoration. The use of such apparent lexical inaccuracies is due to the fact that graffiti is often classified and defined as a form of jietou yishu 街头艺术, or “street art”19Street art (jietou yishu 街头艺术) – A mass media term that tries to define all the art forms performed in public places, often illegally and using the most diverse techniques. Born from graffiti writing, it has developed and evolved into different practices over time: sticker art, stencil art, poster art, video projections, sculptures, installations and performances.. In fact, although in the Euro-American context there has recently been a sharp distinction between writing-based graffiti and painted murals, which represent a form of street art, in China this differentiation is not clear-cut and the two forms are often intertwined (Valjakka 2016, p. 358).

The Chinese word for “graffiti writing”, based on the letters of one’s tag and the use of spray paint, is tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写, which is the exact translation of the English expression. Still, it is little used because few artists devote their career exclusively to graffiti writing.

The terms adopted in the legal field are tuxie 涂写 and kehua 刻画 (Valjakka 2014, p. 98), the first recalling the idea of graffiti writing (tuxie literally means “to scribble, scrawl, doddle”) and the latter referring to street art works based on figurative elements. Indeed, kehua means “to depict, portray” and thus, again, brings us back to the art world. In Chinese law, therefore, graffiti are either doodles or fully-fledged paintings with nothing to do with their original function.

Even the word “writer” has several translations in Chinese, once again highlighting how much of a fluid terrain this is. The first is penzi 喷 子, which literally means “sprayer”, that is, someone who uses spray cans. The term comes from the verb pen 喷 (lit. to spray), used by writers to convey the act of graffiti making (Valjakka 2011, p. 77). The Beijing Penzi crew (see Ch. III) made this word part of their name, thus presenting themselves as a crew of “Beijing writers”.

However, Chinese writers mostly tend to define themselves as tuyazhe 涂鸦者 or tuyaren 涂鸦人, meaning “graffitists” or “graffiti writers”. Publications prefer to use the expression tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家, or “graffiti artist”, which again reminds us that the general public perceives graffiti as a form of art (Valjakka 2011, p. 77). Finally, there are two similar words that recall the central element of graffiti, namely writing, and they are xiezizhe 写字者 and xieziren 写字人 (Flowerstr 2017), literally meaning “a person who writes characters”. These two terms refer to the lively debate in Chinese circles around the use of Chinese writing within graffiti. They turn favourably to this idea and bring us back to the original feature of graffiti writing: the importance of writing in order to exist. Our book is inspired by this very concept, and it is the reason why we have favoured the analysis of artists who, first and foremost are – or have been– graffiti writers, and who have used writing as a vehicle for expression, existence, and even a means of subsistence. In this volume, we describe works that have writing as their main element and medium, as we believe that this cannot be disregarded when talking about graffiti; especially in China, where the world’s oldest in-use writing system is still adopted, and writing represents a symbol of individual and national identity.