AFTERWORD

A Guide to Mireille Delmas-Marty’s “Compass”

Diane Marie Amann1Regents’ Professor of International Law, Emily & Ernest Woodruff Chair in International Law, and Faculty Co-Director of the Dean Rusk International Law Center, University of Georgia School of Law; Professeure invitée, Université de Paris 1 (Panthéon-Sorbonne), 2001-2002; member, Réseau ID franco-américain/French-American Network on the Internationalization of Law, 2006-2015.

“We mustn’t forget however that humans are finite – our cognitive capacities are not infinite”2Mireille Delmas-Marty, “Une boussole des possibles: Gouvernance mondiale et humanismes juridiques”,in Une boussole des possibles. Gouvernance mondiale et humanismes juridiques: Leçon de clôture prononcée le 11 mai 2011 [online], Paris: Collège de France, 2020 (generated 28 August 2022). Available on the Internet: http://books.openedition.org/cdf/8988; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cdf.8988. In its French original, the sentence was: “Cette dynamique ne doit cependant jamais faire oublier la finitude humaine car nos capacités cognitives ne sont pas illimitées”. In this volume’s English translation, it reads, referring to the “dynamic” that Delmas-Marty had just posited, “However, the latter must never lead us to forget the inherently human limitedness, since our cognitive skills are not unlimited” (see TO CONCLUDE).. Loosely translated from the French original, this admonition appears in the last paragraphs of the foregoing essay, which was written toward the end of a half-century-long career. What the essay calls “la finitude humaine” arrived for its author, Mireille Delmas-Marty, on 12 February 2022, in a town 250 miles south of the capital where she had entered this world eighty years before. At her death Delmas-Marty was, among many other things, an Emerita Professor of her birth-city’s eminent Collège de France de Paris. Upon her passing the head of France’s Ministry of Justice expressed great sadness, and yet offered this reassurance: “Her works will remain”3For details on Delmas-Marty’s passing, including the quote from Garde des sceaux Eric Dupond-Moretti, see “Mireille Delmas-Marty, éminente universitaire et juriste, est morte”, Le Monde, 13 February 2022, https://www.lemonde.fr/disparitions/article/2022/02/13/mireille-delmas-marty-eminente-universitaire-et-juriste-est-morte_6113501_3382.html..

The editors of this volume, Professors Emanuela Fronza and Chiara Giorgetti, deserve immense credit for helping to assure that this will be so. Their efforts in producing translations of this essay, first in Italian and now in English, will do much to reinforce Delmas-Marty’s legacy among non-francophone jurists, academics, and practitioners of law.

My choice of that last word, “law,” itself merits remark. Though broad in scope, “law” offers the narrowest net available to capture the many subfields to which Delmas-Marty applied her own cognitive abilities. Within that net will be found criminal law, human rights and humans’ duties, liberty/freedoms, climate justice and environmental law, corporate law, migration law, cultural diversity and biodiversity, economic law and political economy, law and empire, public and private international law, regional (dis)integration, law and technology, security governance, peace, prevention and precaution, ethics, legal accountability/responsibility, legal history, logic and empiricism, social-scientific theory, and political-legal philosophy. Delmas-Marty linked up such seemingly disparate disciplines as a matter of course, albeit not via verbose footnotes detailing works of myriad academics; she preferred terse references to thinkers whom she expected her reader already to know, or at least be ready to learn more about. Her analyses moved seamlessly, in time – centuries traversed in a sentence – and in space – the national or infranational level leapt to the regional, transnational, international, supranational, or global level, and then back again.

The instant essay exemplifies that synaptic style and intellectual abundance. It concerns itself inter alia with democracy and populism, with enslavement and eugenics, with the anthropomorphism of the so-called Anthropocene era, and with the borders that have rendered migrants unfree while according to markets significant freedom. The essay criticizes certain state-based endeavors – the United States’ post-9/11 excesses, for instance, as well as the way France chose to legislate against cloning – and then shifts to the promise of inter-state cooperation as glimpsed in instruments ranging from the Nuremberg Judgment of 1946 to the Paris Climate Accords of 2015. The essay additionally considers the 2005 document in which the United Nations asserted that States, in the first instance, and multilateral institutions, in the second, must shoulder a responsibility to protect populations against atrocities. As the essay acknowledges, early applications of the responsibility-to-protect doctrine prompted worries that it had been “stillborn”4See RESPONSIBILIZING GLOBAL ACTORS.. The essay urges the doctrine’s extension even so: in Delmas-Marty’s imagining, not only present and future generations of humans, but also the environment, animals, and other non-human living things, present and future, must enjoy law’s protection.

Such twists and turns in legal reasoning at times may seem disorienting. So too the cited sources for Delmas-Marty’s rich analysis. They include a few of her own works, as one would expect in an essay that initially was drafted as the final lecture in the author’s nine-year tenure as holder of the Collège de France Chair in Etudes juridiques comparatives et internationalisation du droit/ Comparative Legal Studies and Internationalization of Law5See “Mireille Delmas-Marty: Études juridiques comparatives et internationalisation du droit, Chaire statutaire 2003-2011, Professeur disparu”, Collège de France, https://www.college-de-france.fr/chaire/mireille-delmas-marty-etudes-juridiques-comparatives-et-internationalisation-du-droit-chaire-statutaire; Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, “France Diplomacy: Tribute to Mireille Delmas-Marty”, 15 February 2022, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/human-rights/news/article/tribute-to-mireille-delmas-marty-15-feb-2022 (visited 25 November 2022).. But more often Delmas-Marty recalled theorists other than herself, many but not all of them French, and many but not all of them lesser known outside continental Europe. The English-speaking reader of course will recognize Charles Darwin, and Columbia Law Professor Bernard Harcourt has a following in the United States6See INTRODUCTION, quoting Harcourt (1963- ) and RESISTING DEHUMANIZATION, quoting Darwin (1809-1882).. That reader is likely to have little acquaintance with the philosophers Paul Valéry or Paul Ricœur, however, nor many of the other Europeans from whose published works Delmas-Marty drew her own deep thoughts7See FOREWORD quoting Valéry (1871-1945), and TO CONCLUDE quoting Ricœur (1913-2005).. Delmas-Marty understood all this, and perhaps that is why her title conjures a “boussole,” or “compass.” In its essence this essay offers an instrument for the disoriented reader to find orientation – to consider all possible directions in the hope of choosing a better path forward.

Fig. 1. Picture of The Compass of Possibilities of Antonio Benincà (©2021 Château de Goutelas).

That said, a compass can prove an imperfect tool. It cannot guide without a hand able to hold it steady and a head able to interpret its meaning. It is my privilege in this afterword to try to provide a bit of both.

My acquaintance with Professor Mireille Delmas-Marty began when a mutual colleague recommended I reach out to her on learning of my own research into global convergences and divergences in criminal procedure. The millennium was about to turn, and Delmas-Marty, then at Université de Paris 1 (Panthéon-Sorbonne), was directing Corpus Juris, which aimed to synthesize Europe’s diverse criminal justice systems in order to shape a regionwide criminal procedure. (Aspects of this funded project give rise to a few points worth noting: first, that Delmas-Marty attended to law’s technicalities even as she imagined transcending them; second, that praxis and theory coexisted throughout her career; and third, that within Europe her renown as a legal expert was of long standing.) I was then a quite-junior law faculty member, untenured and for the most part unpublished. Still, her welcome was warm and immediate8See Diane Marie Amann, “Harmonic Convergence? Constitutional Criminal Procedure in an International Context”, Indiana Law Journal, 75, no. 3, 2000, pp. 809-73 (thanking Delmas-Marty and the mutual colleague, University of Vienna Law Professor Frank Hoepfel, in the first footnote, and later discussing Mireille Delmas-Marty (ed.), Corpus juris: portant dispositions pénales pour la protection des intérêts financiers de l’Union européenne / introducing penal provisions for the purpose of the financial interests of the European Union, Economica, 1997). Subsequent Corpus Juris publications would be co-edited with Utrecht Law Professor John A.E. Vervaele, much later the author of “Passing of Professor Dr. Mireille Delmas-Marty (1941-2022)”, Association internationale de droit pénal, https://www.penal.org/de/passing-professor-dr-mireille-delmas-marty-1941-2022 (visited 26 November 2022)., and I flew across the Atlantic for a sabbatical year as a Sorbonne professeure invitée in 2001. The terrorist attacks of that September ruptured legal assumptions which many had thought settled, and within this rupture our collaboration found purpose. Others, too, collaborated; Delmas-Marty followed the European tradition of enlisting doctoral students on projects even as she welcomed colleagues from farther afield. Faced with the return of incommunicado detention and makeshift military tribunals, Delmas-Marty thus organized seminars and grands colloques in order to think through what in fact were, and what should be, the interrelations of national and international law legal systems.

When opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq spurred some US politicians to deride France by renaming a certain side dish “Freedom fries”, Delmas-Marty, by then at Collège de France, responded by establishing the Réseau ID franco-américain, or French-American Network on Internationalization of Law. (Similar French-Brazilian and French-Chinese networks ensued.) For years our network of academics, judges, ministers, and diplomats from France and the United States met, in Paris or New York, to explore points of commonality and difference in our legal approaches. We addressed a mélange of issues: from climate change to copyright to the Convention Against Torture, as well as national, regional, and international jurisprudence on matters as varied as radioactive-waste disposal and remedies for violating condemned prisoners’ treaty-based rights. Some topics touched off an inimitable intensity: Where else might one hear US Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer and former French Minister of Justice Robert Badinter heatedly discuss the death penalty, as I once did? Periodic publications memorialized our work9E.g., Mireille Delmas-Marty and Stephen Breyer (eds.), Regards croisés sur l’internationalisation du droit: France-Etats-Unis (Cross-Cutting Considerations of the Internationalization of Law: France-United States), Paris: Société de législation comparée, 2009. On the US kerfuffle that inspired this decade of network roundtables, see Timothy Bella, “‘Freedom never tasted so good’: How Walter Jones helped rename french fries over the Iraq War”, Washington Post, 11 February 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/02/11/freedom-never-tasted-so-good-how-walter-jones-helped-rename-french-fries-over-iraq-war/. As an example of events outside this network, I am compelled to mention her 10 May 2004 convening at Collège de France of “Crime contre l’humanité, génocide et torture”, in which I was honored to lecture jointly with Antonio Cassese, international law professor and President, or chief judge, at international criminal tribunals, on matters related to crimes against humanity, genocide, and torture..

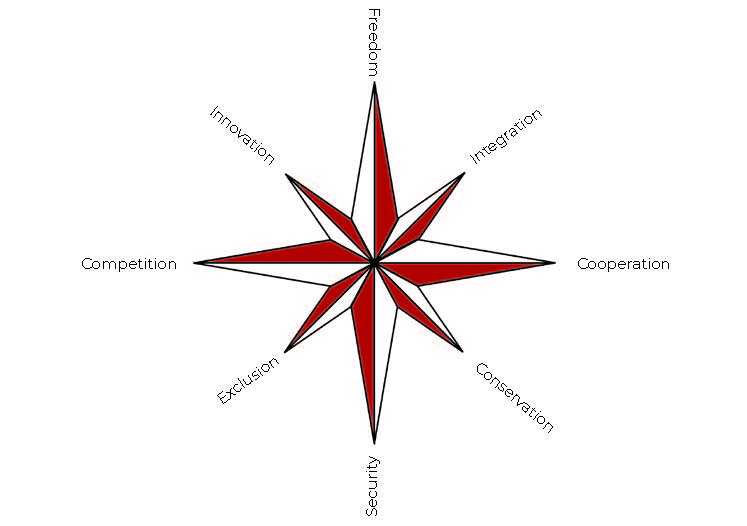

Fig. 2. The Wind Rose of globalization. Schematic representation of the “rose des vents” at the base of the “Boussole des possibles” ‘Compass of Possibilities’), an object-manifesto materalialized by Antonio Benincà. It illustrates the “winds of globalization” composed by the main winds: security, competition, freedom and cooperation; and the “winds between the winds” (vents d’entre les vents) resulting from the intersection between the main winds, such as: exclusion, innovation, integration and conservation.

Throughout this period certain themes resurfaced, even captivated. One was “responsibility”; the other, “human” or, sometimes, “humanity.” Each theme also infuses the instant essay, and so is explored below.

What is human? Humanity? For Mireille Delmas-Marty, these questions comprised the very seeds of inquiry. “Humanity,” she once proposed, “remains a legal concept under construction.”10Mireille Delmas-Marty, Le Relatif et L’Universel, Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2004, p. 76. The translations from all original French sources in this paragraph are my own. In similar vein she started a 1994 article with the claim that “‘man is but a recent invention.’”11Mireille Delmas-Marty, “Le crime contre l’humanité, les droits de l’homme, et l’irréductible humain”, Revue de science criminelle et de droit comparé, no. 3, July-September 1994, pp. 477-90, at p. 477 (quoting Michael Foucault, Les mot et les choses, Paris: Gallimard, 1986). Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations of Delmas-Marty’s 1994 article appear on page 477. Although that claim was not original – it first was uttered by a Collège de France professor whom English-speaking readers well know, Michel Foucault – Delmas-Marty’s article deployed it in a novel way. She observed that “the crime against humanity is an even more recent ‘invention’: codified as a crime for the first time in 1945 by the Charter of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.” In turn, she defined “humanity” as “less ‘the human species,’ in the sense the term is used by the ‘natural’ sciences, than the ‘human family.’” Delmas-Marty expressly borrowed that final term from the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which opens by proclaiming that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” Her article proceeded to examine two prohibitions – of the crime against humanity and of torture or cruel or inhuman or degrading treatment – in an effort “to make clear the irreducible human that underlies legal practices”12Id., p. 478 (emphasis in original)..

Those ideas resonate in the instant essay. “But what about humanity as a whole?” Delmas-Marty asks13See INTRODUCTION.. Her answer rejects “transhumanism” and “post-humanism” as distortions, tending toward “dehumanization,” a process that must be resisted. Indeed, resistance to dehumanization forms the first component of “the triple role” to be played by the “droit en devenir,” or “law in the making” – evolving law – that this essay posits14See INTRODUCTION.. The essay refutes notions that any human may be less than another. No human is “incomplete,” a “monster” who may be subjected to depersonalization; that is, subjected to harm “not because of my deeds, but because I belong to a specific group”15See RESISTING DEHUMANIZATION.. Here as in the 1994 article, Delmas-Marty’s invocation of the Nuremberg precedent occurs within consideration of the “irreducible human”: she demands recognition of each human as human, as a “singular” and “equal” member of the human family. The essay declares these principles “universal […], or at least universalizable” that last phrase an acknowledgment of law’s dynamism16See RESISTING DEHUMANIZATION..

Humans are not all that lives on this earth, of course. It is to be shared with animals and other things, living and inanimate, present and future. And yet it is humans who owe a duty to protect all these others – “this duty falls upon humanity since only mankind is capable of awareness and intentionality”17See RESPONSILIZING GLOBAL ACTORS.. Thus echoing her already-quoted reference to human cognition, Delmas-Marty overtly rebuffed theorists who assert that animals have rights. In exchange, her essay extends humans’ responsibility well past their personal behavior: responsibility also encompasses the legal practices that they adopt – national legislation, international courts, and more – and the entities they establish – States and non-state actors, including corporations. Increasing the responsibility of those who act on a global plane looms as a pre-eminent concern, one that may be implemented through legal techniques like the margin of appreciation and through the third component of law’s triple role; that is, an axiological, or values-based, recalibration of risk.

It is at this juncture, at its conclusion, that the instant essay admonishes us, its human readers, that our cognitive skills are limited. It then quotes Paul Ricœur’s depiction of the gulf between the consequences we intend and the likelihood of unintended consequences. Yet for the reader who knows that this is a closing lecture – as its author well knew – the admonition evokes that other Paul, Valéry. Quoting him quite early in her essay, Delmas-Marty wrote: “we too know that we are mortal. […] And we see now that the abyss of history is deep enough to hold us all”18See FOREWORD (quoting, Paul Valéry, La Crise de l’esprit. Paris: NRF, 1919, vol. XIII, pp. 321-22).. True enough. But we see as well, amid the profusion of ideas this essay provides, an instrument to help guide us as we navigate the shoals of possibility.